In our investigation of sleeplessness and sleep disorders, we reached a crucial point, that is, we do not treat sleeplessness as an isolated phenomenon, but understand it in relation to the initial phase of a treatment (see “Sleep” 1 and 2). Subsequently, what is of greater interest is not sleep as a physiological need, but what this longing for sleeping signifies in each case. This shift of view point ushers into the other side of sleep: namely what the awakening signifies. Is it a return to the reality of the outside world or an escape from some part of reality that resides within us?

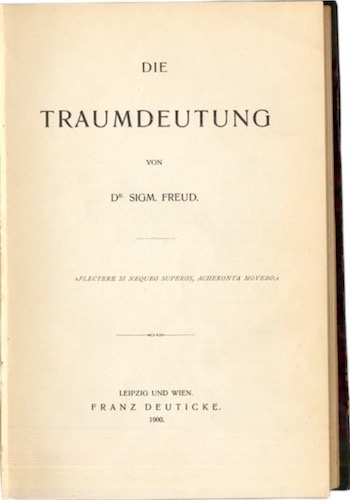

Freud’s concept of the unconscious, as it becomes manifest in dreams, brings a clear understanding of what the complaint about sleeplessness does convey. What Freud states in The Interpretation of Dreams is that dream serves to prolong the sleep and this effect is achieved by producing representations of wish fulfillment. The wish-fulfilment can be however presented in the strangest ways: emotions that do not correspond to the dream scene, strangers who look familiar or a spaceship that feels like one’s childhood home. One common misconception is that the detection of a wish fulfillment, often presented in absurd or surprising forms, is what Freud qualifies as dream’s full interpretation. Such a misconception would reduce the dream to wish-fulfillment fantasy.

In psychoanalysis, the point is that in our particular way to represent to ourselves the external reality, in the way a dream-content is constructed around a wish-fulfilment, there lies the traces of an encounter with the reality of a desire. The unconscious desire originates from elsewhere than in the wish fulfillment of a dream. Dream protects the sleep by coding, by ciphering what is ultimately a productive activity, (Freud calls it dream-work) around some radically incomprehensible kernel, “the nombril of a dream”. The process, that Freud calls dream-work, is there to use any wish and re-cipher it. Desire persists through dream-work and is at the encounter (that may or may not happen) with that seam of reality, the zone or the nexus that joins and disjoins sleep and awakening, forgetting and recollection, self-ideals and the lack of sense. All this dynamic, its complexity, is exemplified by a dream retold by Freud at the opening of the most important Chapter Seven in The Interpretation of Dreams.

The Burning Child Dream

“A father had been watching day and night beside the sick-bed of his child. After the child died, he retired to rest in an adjoining room, but left the door ajar so that he could look from his room into the next, where the child’s body lay surrounded by tall candles. An old man, who had been installed as a watcher, sat beside the body, murmuring prayers. After sleeping for a few hours, the father dreamed that the child was standing by his bed, clasping his arm and crying reproachfully: ‘Father, don’t you see that I am burning?’ The father woke up and noticed a bright light coming from the adjoining room. Rushing in, he found that the old man had fallen asleep, and the sheets and one arm of the beloved body were burnt by a fallen candle.” (Standard Edition, Volume 5, 509)

Let us not forget that Freud has published his seminal work in 1900 in Vienna, the capital of the short-lived Habsburg empire. This empire will officially start what is known as the first World War, fourteen years after The Interpretation of Dreams, in 1914. Burning child dream has since its first publication became charged with connotations that extend to the atrocities of war, apartheid systems, where a morbid predilection for harming children reveals the feeble nature of cruel minds. Unsurprisingly this dream has prefigured quite frequently in the literature and in cinema. Among recent references, we find the documentary The Burning Child (directed by Joseph Leo Koerner and Christian D. Bruun, 2019). In sum, the Burning Child dream has come to denote not only guilt, but to connotate a sense of responsibility for atrocities against children anywhere.

But back to Freud’s own argument.

As Freud points out, the interpretation of this dream does not pose a challenge at first. There is the glare of the fire, perhaps the father suspected that the old man sitting next to the child’s bed was not entirely up to his task. That glare or father’s concern is transformed into a staged dream scene, in which the father fulfills his wish to see the son alive for a second time, followed —surprisingly— by reproaches and probably fragments of memories of sentences uttered by the child earlier in life. But Freud points out that this is not all. He chose to open the chapter with this dream and the rest of the final chapter of the book is to a large extent a comment upon this peculiar dream. What is the fascinating problem in this dream?

The short answer is the awakening. In the Burning child dream, the father wakes up twice, first time in the dream and a second time in the room next to the lying body of his child. There are two awakenings, and then there are also two dead bodies, one in the shape of a corpse in the external reality and another one, resurrected, addressing the father. And we do not skip the fact that there are also two sleeping men in reality as well, one, an older man who is not up to the task of vigil he has taken upon himself and the sleeping father. Thus, reality is a divided one, the reality of the dream and the external reality, both rejoin and vanish in flames.

In the dream of the burning child, the external reality carries out an accident, the candle has fallen over the corpse of the dead child and the bed cloths caught fire. This accident in its chance-like quality, its randomness, which has all the qualities of what Aristotle called “Tyche” (Lacan elaborates this notion in his seminar Séminaire XI, Lesson V). It wakes up the father in the dream, the shadow of the flames over the closed eyes of the father, and the emergence of the son in flames reproaching him, whereupon the father wakes up.

Lacan stresses in his elaborations this moment of awakening as a pivotal point. Between perception and consciousness, the moment of awakening from the dream is like a fleeting lapse of time when we know who we are, but the reality appears as withdrawn, in abeyance (see Séminaire XI, Lesson V). Freud’s “primary processes” reaches an end point at this fleeting lapse. This moment, accidentally actualized in the dream and by the flame, is as Lacan says, that which causes a fire elsewhere, in the reality of the dream. Noteworthy is to underline where the unconscious has been situated, not in some romantic deeper layers of the soul, but as an interruptive point between the representation of an external reality through perception and the moment we reconstruct ourselves, nest ourselves, as a consciousness in that representation at the wakening.

In sum, there are two points to underline. Firstly, life is not only a series of representations and fantasies, psychoanalytic interpretation is about working through fantasies guided by the compass of the accidental encounters with the real. In other words, this is our critique of quite popular notion of an entirely simulated, algorithmic world, best exemplified by the movie The Matrix (1999) or by philosophers such as Jean Baudrillard (Simulacra and Simulation, 1981). Such a simulation may work for a while, for instance through mass media or a systemic denial of facts of life, but the real will catch up at the next turn of the road like an unsettling incarnation of Gödel’s incompleteness theorem. Even if all humans turn away in silence, the stones will still cry out.

Hence, the burning child, resurrected to reproach the father who hadn’t lived up to his role; actualizes the weight and meaning of father as a symbolic instance that each particular father unconsciously tries to live up to. That is what the father in the dream encounters, the question of his desire beneath a sense of guilt: how am I defined as a father in relation to a dead son, when I wake up? This invisible, but real question pierces through the representation of reality in the consciousness, the reflection of the flame in the next room, addresses the sleeping person at the level of his unconscious desires. If your being awake is the same as in a sleeping state, then why should you sleep, during which dreams may bring up some real concern that you don’t want to know of? You don’t take the risk of falling sleep, because you don’t want to know. And when you are at sleep, the same conflict re-emerges on the other side, on the side of awakening, the frontier that presents the gap between consciousness, self-identity and the reconstruction of the perceived reality outside, dream work sets on to create a screen before another threat to our more comfortable blissful ignorance. This logic is not operational at an individual level only, we have mentioned the significance of this dream in historical terms.

The demand or complaint about sleeplessness can be thus understood by the field opened up by the Freudian unconscious and its further logical development in Lacan’s clinic.

In more classic Freudian terms, insomnia is an expression for a defensive anticipation of what the moment of awakening may bring about. There is a representation of reality in which we are comfortably lodged, in which we also suffer from our unattended desires. Ego’s defensive anticipation tries to circumvent that risk, and per usual, it cannot but overshoot its goal, in order to preserve the comfortable image of the Ego that both soothes and constrains us, it will seriously disrupt a physiologically vital need. The tension caused by this anticipatory defense may cause such an anxiety that in turn falling asleep becomes an agonizing mystery for the person.

Finally and as a conclusion: What differs psychoanalytic therapy in practice from other orientations is that we take person’s complaint about sleep problems or any other symptoms absolutely seriously, literally and factually as a starting point — a stolen letter in plain sight. Theories are there to be forgotten in an active manner during the clinical practice. They are perhaps more like ladders that you use to reach a certain place. What ultimately matters is the wager that you may want to really know why the stones cry out.

References

Freud S. The Interpretation of Dreams 1981 (1900). The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol V. London: Vintage.

Lacan, Jacques. Séminaire XI, Quatre concepts fondementaux de la psychanalyse. Paris: Le Seuil.