In the clinic, we encounter people, especially young adults, who complain about an invasive state of boredom. Simple tasks appear to them as tedious. Existential meaningless, powerlessness or moral distress, all are affects that accompany a lack of goal and orientation in life. Before hastening towards a brand such as “depression” and add new classificatory attributes as in DSM V, we need to pause and examine the broader context surrounding this term “depression”.

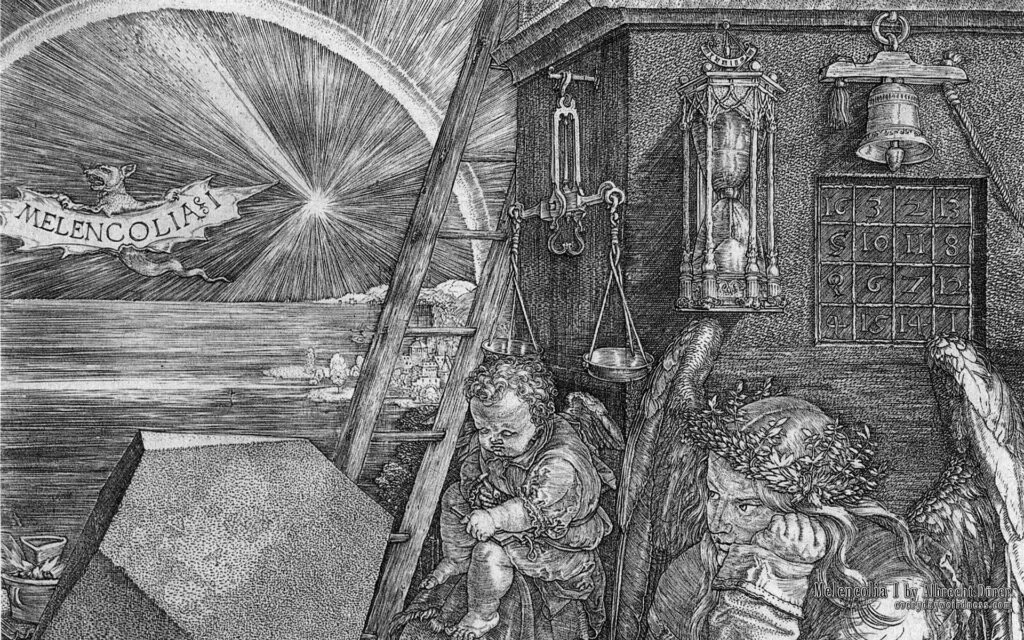

Since the last decade of the last century, about 30 years ago, the term depression started to become popular, first in the mental classifications, and later as a word in the everyday language. One of the earliest, and therefore more enlightening occurrences of this new sensibility in the contemporary culture, was the American novelist William Styron’s short memoir, Darkness Visible, from 1990s. What Styron described as “so mysteriously painful and elusive in the way it becomes known to the self – to the mediating intellect – as to verge close to being beyond description.”, resonates even today as a more insightful description than medical manuals. Likewise, the realisation that the medication with Benzodiazepines were more directly responsible for his suicidal impulses than his devastating mental state made the book an eye opener. At least in the English-speaking world, Styron’s memoir signaled a new genre of literature: memoires of depression, new metaphors about darkness, abyss, and demons. That was the reception of the times and it tells us something about the Zeitgeist, now definitely marked by a form of melancholia that was branded depression.

One of the more well-known memoirs in the wake of the immense success of Styron’s book, was the novelist Andrew Solomon, The Noonday Demon: An anatomy of Depression. The book exists even in a Chinese translation. For Solomon, “Depression is the flaw in love. To be creatures who love, we must be creatures who can despair at what we lose, and depression is the mechanism of that despair”.

During these thirty years, Mass media and pre-dominantly American medical establishment came increasingly to speak of depression in terms of a biological disease, trying to attribute the term “depression” to chemical interactions in the central nerve system. The surge of what was now diagnosed as depression corresponded to the production of a new generation of drugs during the same period. These so-called third generation drugs, such as Prozac or Zoloft, mainly are serotonin inhibitors. The category of “depression” in contemporary diagnostic system is therefore epistemologically tied to a certain belief in chemical aetiology.

In this context, standard models such as DSM plays an important role in propagation of a specific culturally determined term on a global scale. Moreover, DSM in its fifth edition, added even more classificatory subgroups and almost entirely did away with melancholia as a category. Indeed, DSM’s behaviorist and functionalist approach impoverished the classic psychiatric language, where we did have recourse to above all melancholia and melancholic psychosis. This much said, DSM has accepted the term used in China (神经衰弱) and Japan, which barely connotates a mental disorder and is based on the 19th century classification of neurasthenia. But the more serious issue in a functionalist, behaviorist approach— DSM for instance— is more severe cases of melancholia can completely be missed. A person may appear absolutely calm, when a decision to harm himself or herself has already been taken. Even the close relations may not detect anything else than a positive and unusually calm. This is where a psychoanalytic approach is more precise and realist, because, its method of diagnosis and treatment is based on a comprehensive approach, where structure of the subject plays the central role.

This background should make us cautious about the inflation of the word depression in everyday language at a global level, without neglecting the serious suffering that is involved in a person’s life history. The 30 odd years of depression wave, its coincidence with the introduction of new pharmaceutical drugs (which is not at all aleatory), has had a global impact far beyond North America and Northern Europe. As a result, a neurological and behaviorist paradigm let us believe that we can dispense with a deeper understanding of a person’s suffering within her cultural and historical context. Hence, we find far outside the American culture scientists who comment on the tragic suicide of a pop star, telling the general public that “depression” is caused by a central nerve system malfunction, even though this malfunction cannot be located or identified. In other words, the malfunctioning of the central nerve system is evidently not — but must be— the cause of a complex system of affects, thoughts and acts. Unwarranted stipulations of this kind are unlikely to be helpful for the well-being of anyone.

Clinic and Depression

At the same time, it is a clinical fact that there are more people, especially younger adults, who increasingly conceive themselves in terms of an aimless, desireless depressive state, followed by acute feeling of powerlessness and lack of initiative. Psychoanalysts encounter mainly one of the two following situations: More often, a psychoanalytically well-oriented interview reveals that patients or clients who initially complained about “having a depression”, suffer from other relational or pathological symptoms. Most prominently but not always, a traumatic event or an unfinished labor of mourning can lie behind. This is called a reactive mental distress, rather than any melancholic diagnosis. The second situation, the cases of melancholia with or without psychotic episodes, undeniably exist. Strangely enough, some of these cases would be mistakenly classified by American functionalist models (such as DSM) as borderline personality. Hence, a deeper and more scientific understanding of phenomena that are classified as depression is required.

For Freud, the main mechanism involved in melancholy is a psychological function known as inhibition, the repression of unconscious impulses, and deeper the narcissistic identification. A repression that is a function of an ideal self-image, an ideal Ego. Subject, as an active agent, fades away, and fall into what the earlier mentioned novelist qualified as pure despair.

Lacan who tried to logically articulate the implications of psychoanalytical clinic and draw its full conclusions, follows up this inhibitory mechanism to its root, to the relation between desire and the object of desire. The object, as a loss, the object of what would be called the object of jouissance, overwhelms the melancholic subject, as the subject cannot assume the loss as such. Any new loss, be it the loss of an important person in subject’s life or a trivial loss, re-actualizes the fundamental incapacity of the subject to face the original and presupposed lost object. The subject does “know” that mourning is the symbolization of this loss, but he or she unconsciously refuses this option. Instead, this fantasized and out of reach object of an absolute completeness, imagined in corporal terms, “now only transcends the subject, whose command escapes it – and whose fall will drag the subject into precipitation-suicide, with all the automatism, the necessary and fundamentally alienated character of melancholic suicides.” (Séminaire X, 388). It is then not surprising that Lacan notices the utterly ethical dimension of subjective act in melancholy and depression. This ability towards an act in its full subjective dimension is inhibited, held back, with enormous expenditure of person’s affective and intellectual capacity (Télévision 38-39). We are not going to delve into a more minute theoretical discussion or a detailed description of the direction of cure at this point in a social media article. It suffices to mention that the Spinozist concept of conatus and a Marxian argument on the relation between productive forces fettered by social relations both become highly relevant at this juncture. If I mention these two last authors, it is because depression, especially the depressive states that is more frequently reported in young adults, as we have seen, cannot be grasped outside the context of capitalist social and historical reality. It is not a coincidence that the more the contemporary culture seduces us to purchase satisfaction, and commands us — like an internalized and unspeakable command from what Freud called Super Ego— to “enjoy” the objects produced by industry (including reading social media), the more the notions of meaningfulness or happiness seem out of reach, the more spiritual cults grow and the more overwhelming the object of a primordial loss and separation from absolute happiness become. The devastating effect of this logic is sensed by human subject in contemporary culture. The melancholic defiance of this loss, is not a viable or livable solution, as that repressed loss returns, now as a devastating, invasive object that only can be overcome through an ultimate, tragic short-circuit; the act of suicide.

- Styron, William. Darkness Visible. Random House. Random House Press. 1990.

- Andrew Solomon, The Noonday Demon: An Anatomy of Depression, Chatto & Windus, 2001. Chinese (PRC) translation: 走出忧郁. Translator: 李凤翔. Chongqing: 重庆出版社. 2010.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition, DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

- Freud, S. (1926). Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. Vol XX. London: The Hogarth Press.

- Freud S. Mourning and melancholia. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol XIV. London: Vintage.

- Lacan J., Le Séminaire, livre x, L’angoisse, texte établi par J.-A. Miller. Paris: Le Seuil. 2004.

- J. Lacan, Télévision, Paris: Le Seuil. 1973.