I am a memory come alive, hence my insomnia.

The Diaries of Franz Kafka

In the previous article, we spoke of sleeplessness and the global rise in the consumption of sedatives. For understanding how psychoanalysts work, we made a distinction between the complaint about poor sleep or sleeplessness and the physiologically and historically determined modern conditions of human life.

This distinction is decisive from a clinical point of view. Our immediate interest, as a psychoanalyst or psychotherapist is the complaint about sleeplessness or rather, the socially circulating desire for sleeping beyond any biological parameter. Otherwise, there are people who, due to their working situation, cannot afford the physiologically required sleeping hours, which has obvious psychological consequences. A change of working or life circumstances, if possible, is a good piece of advice, but advice is not the primary, sole objective of a psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy. Psychotherapy is not consulting, it is counselling, which means a carefully and theoretically well-informed working through unconscious processes and affections based on a differential diagnosis, so that a person can be able to love and to conduct an active life.

Moreover, the physiological need for sleep cannot be isolated from a person’s social and affective life. The medical model is after all only a model based on the abstraction of biological life. There are many people whose creativity seems to flourish in spite of their sleeplessness. Franz Kafka complained constantly in his Diaries about insomnia. But the same diaries reveal also a certain undercurrent that connect his insomnia to his literary production.

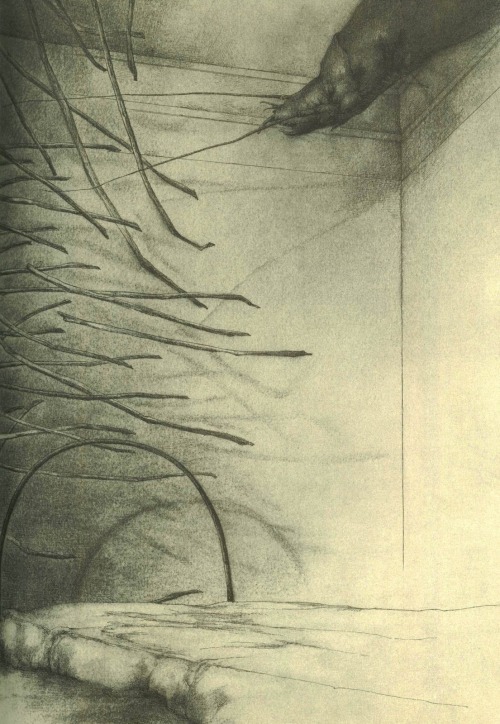

José Hernàndez, Illustration for Kafka’s Metamorphosis in Borges’ Spanish Edition

Returning to the therapy room and the complaint about sleeplessness, let us suppose for the sake of argument, that the subject (a patient or an analysand) complains about chronic sleeplessness. Different methods, besides the medical treatments can be engaged. We have treated the medical treatments and the risks of a misconception that may usher into drug over-consumption in the previous article. We may view the matter as the following: the person simply wants to sleep but is unable to do so due to wrong behavioral patterns.

This is how behaviorists would view things. We can then believe this person has to solve the conflict between a healthy part of his personality, which identifies the need of sleep, and an unhealthy or mislead or damaged part that does not recognize this physiologically vital need. Consequently, we can indulge into something that ultimately is akin to educating, in many cases— but perhaps not Kafka’s— this will probably be a good enough short-term solution, sweeping and tucking away the real concerns for a while and before they show up elsewhere in the person’s life. We are not criticizing its short-term effectivity, on the condition that we know the price that is paid, a certain pale rigidity and submissiveness that necessarily follow from an act of disciplining and managerial approach to people’s visible behavior. Sometimes, some people prefer this solution.

Similar to this educational approach, but with a more nuanced attention garnered for emotional dimension of the matter, is the broad spectrum of ego-psychological approaches. They rely on a so-called alliance with the “healthy and mature part” on an emotional level, whereas the behavioral therapy limits itself to the external behavior and tries to harness and control the socially unacceptable behavior, these approaches try to strengthen the ego by a higher awareness of emotions we experience.

A psychoanalytical treatment differs from both of these two approaches without ignoring the importance of giving advice or the significance of emotions or self as an object. The difference consists of the fact that it is the subject’s desires, in interaction with the surrounding social environment that decide both diagnosis and the mode of intervention. Neither behaviors, nor emotions cover the broad register of fantasies and inner conflicts that determine a symptom’s formation such as sleeplessness. A certain behavior cannot be isolated from a longer life trajectory, it is in reality determined by how a person represents her his being in a social context through his or her phantasies. How he or she sees herself through the eyes of others and act or react upon it by being positioned in a place from where he or she wants to be seen.

The theory’s role is not to cover up the encounter with the unconscious, an encounter that is present in all seemingly trivial complaints, such as the complaint about sleeping problem. In short, theory’s function is to help to see the unique situation of a person, to minimize theory’s presence as much as possible, and to listen to what has been said by the person. Notions such as mind/emotions versus body, or a division into healthy and unhealthy part of the ego, even though they sound simple and clear, actually complicate the matter. Mind-body dualism, be it a metaphysical prejudice or a postulate, would be best left to speculations by philosophers. The same is true about the notion of “self”. Concerning the affections and emotions, their weight is undeniable in any serious analysis. Empathy, rather than a skill, is an ethical decision by the caregiver. However, if the therapist understands her or his role only to affirm or to articulate emotions, as a part of the self-conscious ego, this language of feelings strengthens the narcissistic ego, which was in the first place is responsible for the sleeping perturbations. The idea that an affective contradiction within the ego can be resolved by some normative reality-check represented by the analyst, rely upon the myth of a self-mirroring consciousness.

However, Freud’s discovery of the unconscious desires, has shown that this same self-consciousness with its critical voice and its harsh judgments based on an internalized ego ideal (Freud’s term is “Ichideal”), all too often is the agent that causes the person’s suffering, among which sleeplessness is one of the symptoms. Beyond a therapy of feelings stand a super-ego and a thinly covered moralistic superposition.

In reality, these theories create a castle that prevent us from seeing the caregiver’s own anxiety at the encounter with a suffering individual. And it is this anxiety that blocks the caregiver’s attention, now eclipsed behind a myriad of relevant or irrelevant general and abstract notions. In psychoanalysis, more than uttering a word, it is about a genuine listening to the fantasies and structures that fixates the form of suffering the subject is complaining about. Hence, the recourse to a notion of cognition or “feeling in the room” expresses a resistance on the side of the analyst or therapist at a certain turning point during the therapeutic process.

Psychoanalysts would view it as a part of a transferential situation (transference, discovered by Freud is an observation that is at the onset of psychoanalysis, see further Freud’s Studies on Hysteria). We are not going to be technical at this point. Instead, and in a short hand version, we identify this turning point as a point of impossibility invoked by the spoken words in the analysis, a want of a unitary self shattered by the persistence of the symptom (in this case, sleeplessness) beyond any advice or meaning. Something is out of joint, something that should not be there, like a ghost that returns and hunts us. The traumatic experience means something that we don’t know or that we only can formulate as a dead-end, an impossible either-or. This is what Lacan called the real. A concept that broadens our perspective so that this encounter with the impossible is not buried under prejudices or ideological or moral prescriptions. The complaint about sleeplessness is above all then approachable as a question, a question concerning what it means to be awake for the person complaining about it, and what happens in that twilight land that unites and separates sleep from wakening. It is reasonable, even for ardent defenders of a crude biologism, to assume that we sometimes —by accident— don’t want to be reminded of a subjacent, dispelled or denied traumatic experience and prefer a dreamless sleep.

Once we relinquish the idea of our beings as instances of a pure, immutable identity that needs to be managed either in behavioral, biological or emotional terms, then we realize the material significance of aleatory movements that reveal the presence of an underlying structure. Swerves and emptiness become equally meaningful as the idea of a world saturated by fixed essences and prejudices about our and others’ self-identical being (that is one of the roots of all racism). Since Pre-Socratic, Chinese and Indian thinkers’ time, we have been provided by an alternative view, which does not aim to do away with a certain structured randomness, the unexpected encounter with the impossible — this is accidentally more in line with modern so-called hard sciences.